2021-04-03

Hello everyone. In this article, I will try to explain what I know about music generation with LSTM (long short-term memory) based RNN (recursive neural networks). Let's first examine what kind of information contains the dataset I have used in the training phase of the model.

As we all know, music is represented by notes. I preferred to use an alternative note system in the dataset, known as the ABC notation, instead of the classical notes in the style of Do, Re, Mi, etc. In ABC notation, numbers, and special characters are used along with letter notations from A to G to represent the given notes. Each letter corresponds to classical notes such as Do, Re, and Mi in classical notes. In addition to the notes that make up the melody, other units are used as additional information; reference number, composer, origin, note length, tempo, rhythm key, ornament, etc. Each of these values constitutes the features of our data set. The ABC notation is often used to represent traditional folk music. The dataset I have used is compiled from Cobb’s Irish Folk Music [1]. Below you will see sample music expressed with ABC notation from the dataset.

X:1

T:Alexander's

Z: id:dc-hornpipe-1

M:C|

L:1/8

K:D Major

(3ABc|dAFA DFAd|fdcd FAdf|gfge fefd|(3efe (3dcB A2 (3ABc|! dAFA DFAd|fdcd FAdf|gfge fefd|(3efe dc d2:| ! AG|FAdA FAdA|GBdB GBdB|Acec Acec|dfaf gecA|! FAdA FAdA|GBdB GBdB|Aceg fefd|(3efe dc d2:|!

Here, we are facing a problem: Can our computers make sense of data that contains letters and special characters? Since we are going to multiply the features by the weight values, B x 0.23 would be an illogical operation, it seems unlikely, doesn't it? For this reason, we must bring the data into a format that the computer can understand. Just as computers represent images as matrices containing pixel values, we will assign a numerical value to each note in the data set, whether it is a letter or a special character. This operation is known as encoding in the literature.

To perform the encoding process, we first collect all the songs in a single list with the help of the code snippet below. After extracting each original character in this list and sorting it from small to large, we throw it into the vocab variable. The vocab variable contains unique characters that carry information and represent our songs. Then we define the operations that allow us to assign numerical values to these unique characters, that is, to perform the encoding process: char2id, which maps characters to numbers, and, idx2char which maps numbers to characters.

# Join our list of song strings into a single string containing all songs

songs_joined = "\n\n".join(songs)

# Find and then sort all unique characters in the joined string

vocab = sorted(set(songs_joined))

print("There are", len(vocab), "unique characters in the dataset")

# Define numerical representation of text data so that can be process by computer

# Create a mapping from character to unique index.

# For example, to get the index of the character "d",

# we can evaluate `char2idx["d"]`.

char2idx = {char:id for id, char in enumerate(vocab)}

# Create a mapping from indices to characters. This is

# the inverse of char2idx and allows us to convert back

# from unique index to the character in our vocabulary.

idx2char = np.array(vocab)

print('{')

for char,_ in zip(char2idx, range(20)):

print(' {:4s}: {:3d},'.format(repr(char), char2idx[char]))

print(' ...\n}')

Below you can see each unique character in the dataset and their corresponding numerical value.

{

'\\n': 0,

' ' : 1,

'!' : 2,

'"' : 3,

'#' : 4,

"'" : 5,

'(' : 6,

')' : 7,

',' : 8,

'-' : 9,

'.' : 10,

'/' : 11,

'0' : 12,

'1' : 13,

'2' : 14,

'3' : 15,

'4' : 16,

'5' : 17,

'6' : 18,

'7' : 19,

...

}

Let’s combine the above-mentioned operations into a function to be more modular and organized.

def encode_string(string):

"""

A function to convert all the song strings

to a vectorized and numeric representation.

Args:

string -- List of strings

Return:

encodeded_string -- Encoded list of strings

NOTE: the output of the `vectorize_string` function

should be a np.array with `N` elements, where `N` is

the number of characters in the input string

"""

encodeded_string = np.array([char2idx[char] for char in string])

return encodeded_string

encodeded_songs = encode_string(songs_joined)

print ('{} <--- characters mapped to int ---> {}'.format(repr(songs_joined[:10]), encodeded_songs[:10]))

# Check that vectorized_songs is a numpy array

assert isinstance(encodeded_songs, np.ndarray), "returned result should be a numpy array"

Following the character encoding process according to the assignments stated before, our sample data including letters, numbers, and special characters transformed like below. In this way, after preprocessing operations performed on our dataset, we now made our dataset ready to use.

'X:1\\nT:Alex' <---encoding---> \[49 22 13 0 45 22 26 67 60 79\]`

Our next step is to break down the text containing the songs into sample batches that we will use during the actual training. Each input string in which we feed our model contains as many characters from the text as the number of seq_length. Also, to predict the next character, we need to define a target sequence for each input sequence to be used in the training of the model. For each input string, the corresponding target string will contain characters of the same length, except if one character has been shifted to the right.

To do this, we have to divide the text into seq_length + 1. Assuming the variable seq_length is 3 and our text is Helsinki, our input string will be Hel and the target string will be els. The function, whose definition you can see below, allows us to convert this string stream into arrays of the desired size.

def get_batch(encodeded_songs, seq_length, batch_size):

"""

Batch definition to create training examples

"""

# The length of the vectorized songs string

n = encodeded_songs.shape[0] - 1

# Randomly choose the starting indices for the examples in the training batch

idx = np.random.choice(n-seq_length, batch_size)

# A list of input sequences for the training batch

input_batch = [encodeded_songs[i : i+seq_length] for i in idx]

# A list of output sequences for the training batch

output_batch = [encodeded_songs[i+1 : i+seq_length+1] for i in idx]

# x_batch, y_batch provide the true inputs and targets for network training

x_batch = np.reshape(input_batch, [batch_size, seq_length])

y_batch = np.reshape(output_batch, [batch_size, seq_length])

return x_batch, y_batch

x_batch, y_batch = get_batch(encodeded_songs, seq_length=5, batch_size=1)

for i, (input_idx, target_idx) in enumerate(zip(np.squeeze(x_batch), np.squeeze(y_batch))):

print("Step {:3d}".format(i))

print(" input: {} ({:s})".format(input_idx, repr(idx2char[input_idx])))

print(" expected output: {} ({:s})".format(target_idx, repr(idx2char[target_idx])))

Sample input series on batch created for trial purposes and expected values:

Step 0 input: 18 ('6') expected output: 0 ('\\n')

Step 1 input: 0 ('\\n') expected output: 45 ('T')

Step 2 input: 45 ('T') expected output: 22 (':')

Step 3 input: 22 (':') expected output: 32 ('G')

Step 4 input: 32 ('G') expected output: 73 ('r')

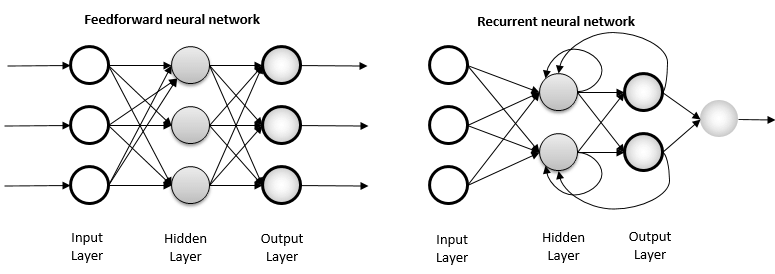

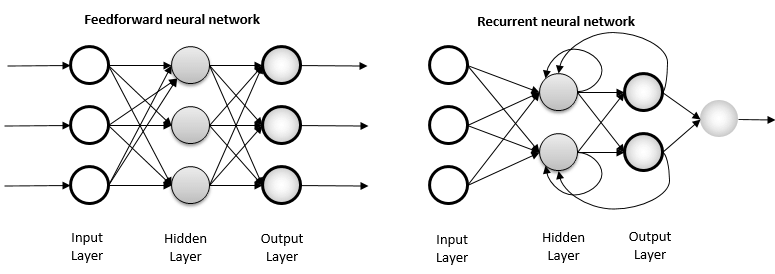

Now it's time to design our model. We could use classical artificial neural networks (ANNs) in our model, but since the melodies we call music consist of a series of repeating notes, the classical ANNs using the feed-forward technique are somewhat dysfunctional for this problem. The notes that make up our music are not independent of each other, on the contrary, they are arranged one after the other in a way to adapt to the previous one. That is why in our model we will use RNN, which is a more advanced artificial neural network algorithm, that provides a very good solution to such sequence and repetition problems. In addition to classical neural networks, this algorithm can take the output of the previous node as input, while at the same time taking its output as an input for the nodes that are in parallel and after it. Below you can find a diagram where you can see the difference between feed-forward neural networks and RNNs.

Although it offers a great solution for some problems, RNNs have some missing points. One of them is the ability to carry the information of array elements up to a certain past point to the next steps, in other words, their memory is very short and the algorithm starts to be difficult when it comes to using the previous elements. As a solution to this, gate cells have been developed aiming to solve exactly such problems. There are several types of door cells, for example, LSTM and GRU. We will use LSTM of these, and I avoid going into the details of this because it involves some complex mathematical operations and these are not our focus now. But for some intuition, I leave below a visualized LSTM gate cell.

You can see the summary of our model below.

Model: "sequential"

_________________________________________________________________

Layer (type) Output Shape Param #

=================================================================

embedding (Embedding) (32, None, 256) 21248

_________________________________________________________________

lstm (LSTM) (32, None, 1024) 5246976

_________________________________________________________________

dense (Dense) (32, None, 83) 85075

=================================================================

Total params: 5,353,299 Trainable params: 5,353,299 Non-trainable

params: 0

_________________________________________________________________

When the training is over, the model presents us with the pieces of music produced by the based RNN model as a string. We copy this sequence and paste it into a notebook that we will open on the computer and save it as .abc extension. After this process, you can listen to the music track. Remember, the model may not produce a successful result every time, it may be necessary to produce several times to produce a melody with a nice sound. Have a nice try.

Unique music pieces that emerged at the end of the training:

I did not want to share all the codes here because the article will be too long. However, I shared the dataset and the notebook on GitHub for everyone to experiment. See you in the next article.